Headless CMS scales and improves WPWhiteBoard’s content distribution, flexibility, and personalization

Nikhil Gandal

We’ve all sat in that retrospective. You know the one where the air is thick with frustration. Maybe you’re the Product Manager looking at a feature that launched to crickets because users couldn’t figure it out, despite the rigorous spec.

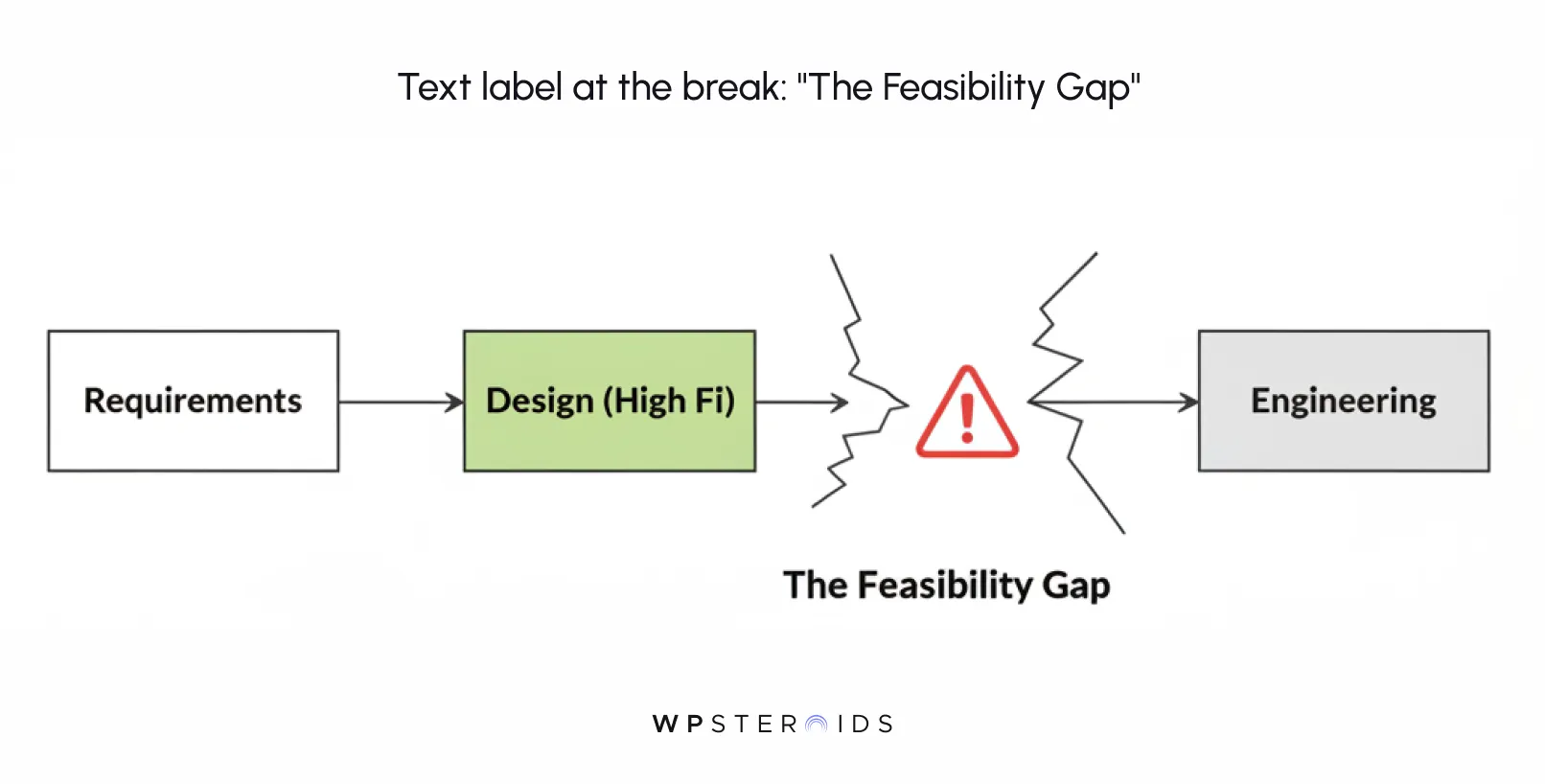

Or maybe you’re the Designer watching your polished, high-fidelity prototypes get slashed to ribbons by Engineering because the backend architecture "just doesn't support that interaction."

This is the classic, painful standoff of modern product development. On one side, you have the drive for pure functionality. Does the software actually solve the problem? On the other hand, the demand for elegance, can the user navigate it without throwing their laptop out the window?

When these two forces collide late in the process, you end up with "handoff heartbreak." But the truth is, the tension between what a product does and how it feels isn't a necessary evil. It is usually a symptom of a broken workflow.

Here is the core distinction you need to anchor your team:

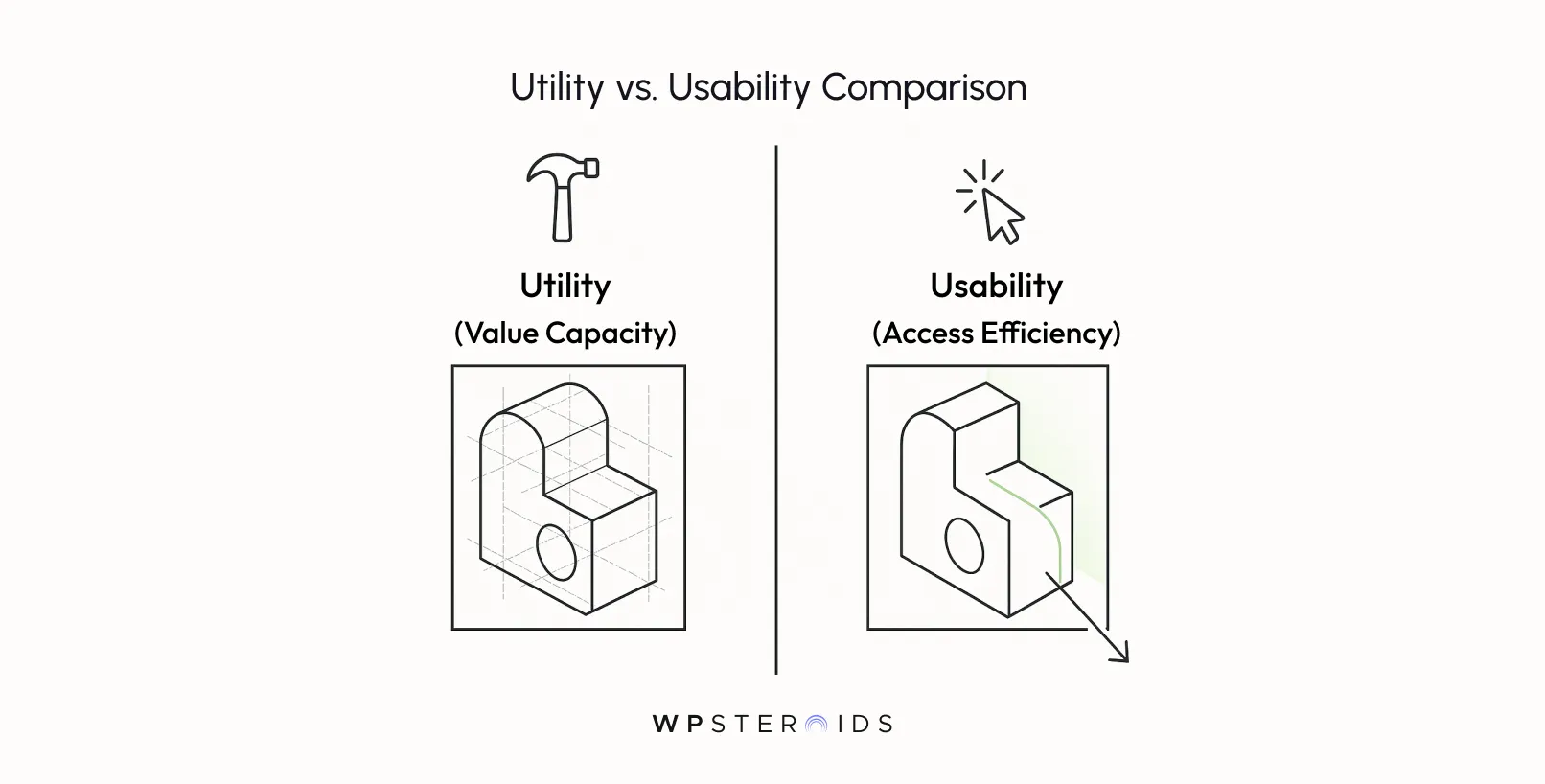

Utility refers to a product's functionality and its capacity to solve a specific user problem, while usability determines how intuitively and efficiently users interact with that interface.

To prevent costly rework, effective design eliminates the trade-off between these pillars by using collaborative "early skeletons" to validate technical feasibility and user value simultaneously.

Most product leaders know the textbook definition of usability. We know that usability is about effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction. But knowing the definition hasn't stopped us from burning cash on rework.

It’s true that users tolerate bad ux if the utility is high enough. Excel is a prime example of this. But in today's market, relying on utility alone is a dangerous gamble. If a competitor offers the same utility with half the friction, your user base will vanish.

You cannot manage what you do not distinguish. For many product teams, "UX" has become a catch-all bucket where business requirements and interface design get muddy. To stop the cycle of rework, you need to be precise about which lever you are pulling.

Think of usability, utility, and accessibility as the pillars of user experience—but they are not identical structural beams. They bear weight differently. Usefulness is your product's purpose; ease of use is its delivery mechanism. And accessibility in ux design is the foundation that ensures anyone can access that utility.

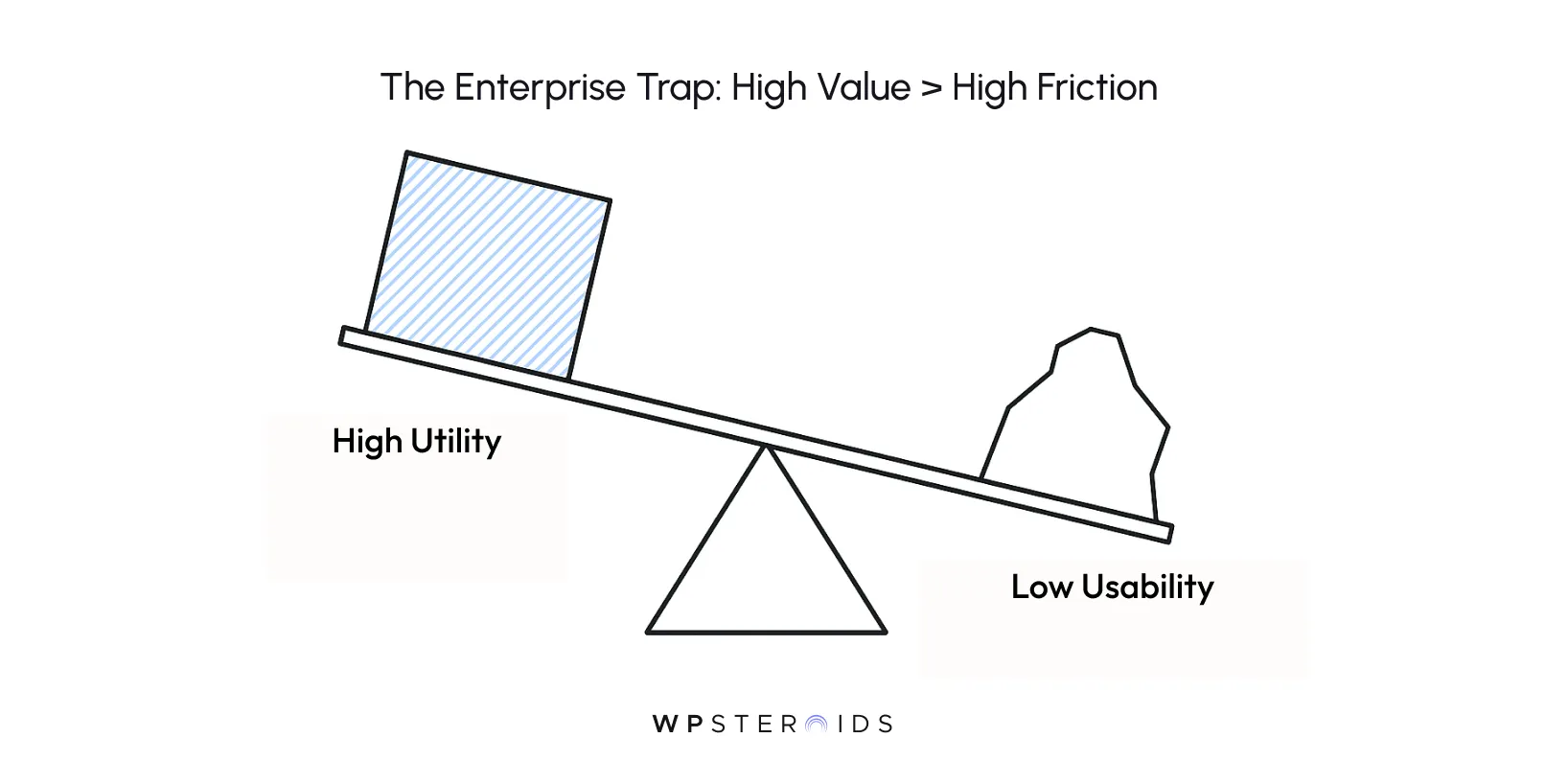

This is most common in companies operating in high utility environments, like complex B2B enterprise software, specialized medical tools, or internal legacy systems.

Here, the utility over usability effect explains why your users aren't churning despite their complaints. They aren't staying because they love the interface; they are staying because the software solves a real problem that no one else solves.

In a 2023 fresh perspective on product strategy, design expert Chris Nodder suggested that prioritizing utility in the early stages can actually harness user patience as a strategic asset. In niche, value-heavy software, your users are essentially willing to "pay" with their patience in exchange for the result.

However, do not mistake this for permission to be lazy. While high utility low usability might survive in a monopoly, it is a fragile existence. The moment a competitor matches your utility with even marginally better ux design, that accumulated accessibility in ux debt will cause a mass exodus.

On the flip side, consider the consumer market. If you are building a to-do list, a weather app, or an e-commerce store, the utility is likely a commodity. Users have a thousand other ways to check the weather.

Here, engagement, retention, and conversions, while heavily dependent on utility, are captured almost entirely by how seamless the experience is.

For these products, why usability is important is a matter of immediate survival, not just long-term retention.

Imagine you are building a custom house. In a traditional process, the architect spends months drawing up elaborate blueprints—floating staircases, floor-to-ceiling glass walls, specific imported materials.

The client signs off, thrilled. Then, the builder arrives on site, looks at the plans, and says, "This soil can't support that weight," or "That glass doesn't exist in these dimensions."

The result? Demolition. You have to tear down the frame you just started or hack the design to pieces to make it fit reality.

This isn't just a communication failure; it is a structural failure. It is designing what cannot be built without significant compromise.

They technically capture every data point needed (utility), but the interface is often a cluttered disaster of tabs, dropdowns, and modal windows that force doctors to click dozens of times for a simple task.

Why? Because the "utility" (compliance and data storage) was defined by stakeholders, and the "usability" was plastered on top later by developers trying to fit endless requirements into a legacy framework. The result is a product that users hate but are forced to use.

Conversely, look at the many "Dribbble-first" mobile apps that launched with beautiful animations and ground-breaking gesture controls, only to fail because they devoured battery life or crashed on older devices. The design prioritized aesthetic usability, but the engineering utility couldn't sustain it in the real world.

If you could visualize your customers' frustration when they encounter these compromised interfaces, you would see that the cost isn't just internal. Every moment of friction is a micro-transaction of trust you are losing.

We need to stop paying this tax. We need a way to validate that our blueprint matches the soil conditions before we pour the cement.

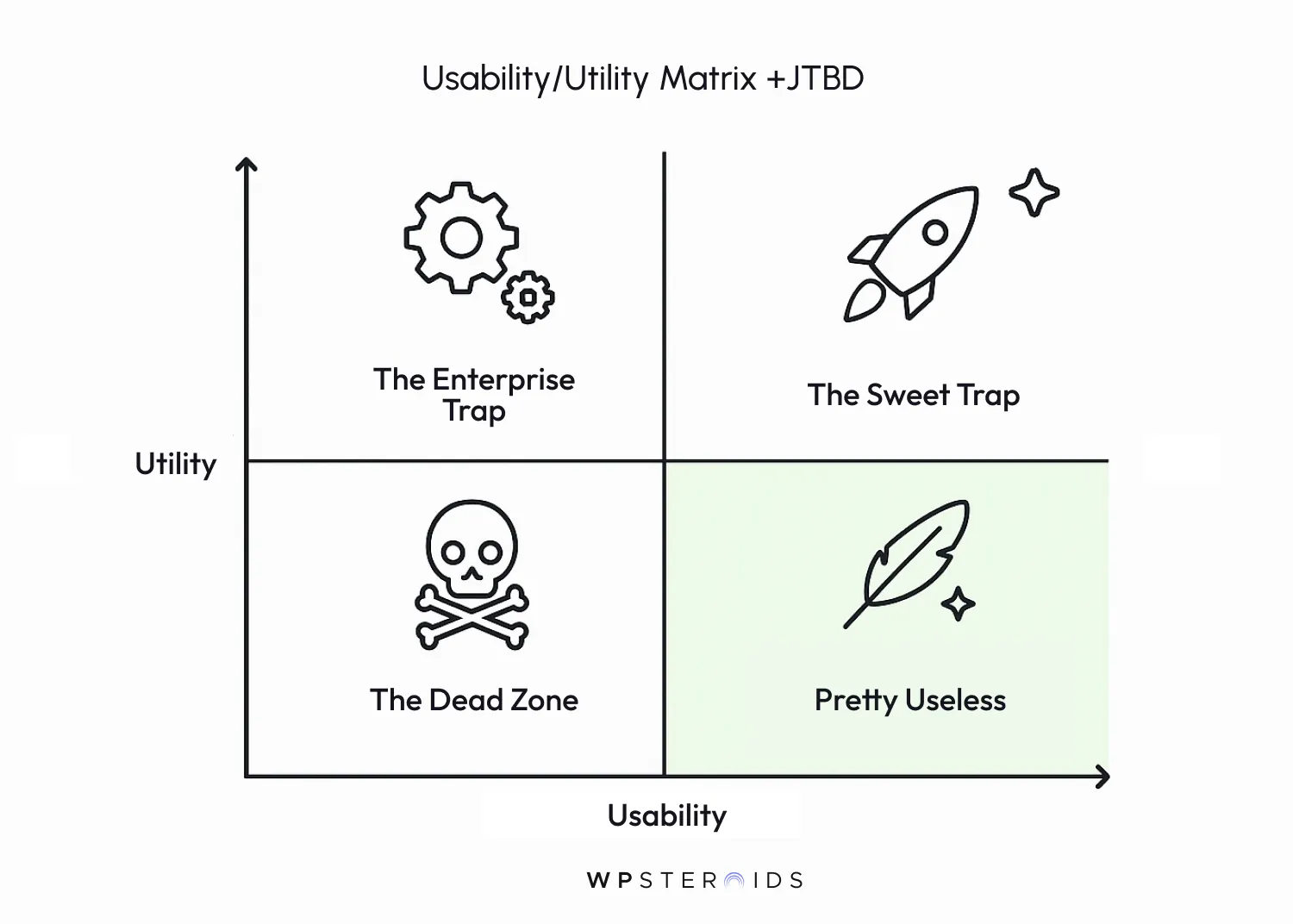

You don't need to rely on gut feeling to determine if you are building the right thing. You need a map. This is where the Usability vs Utility Matrix becomes your most valuable strategic asset.

Visualize a simple four-quadrant chart. On the vertical axis, you have Utility (Value). On the horizontal axis, you have Usability (Ease of Use).

Before you worry about button placement, you must verify that you are establishing product value. If the underlying utility is flawed, optimizing the interface is like rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

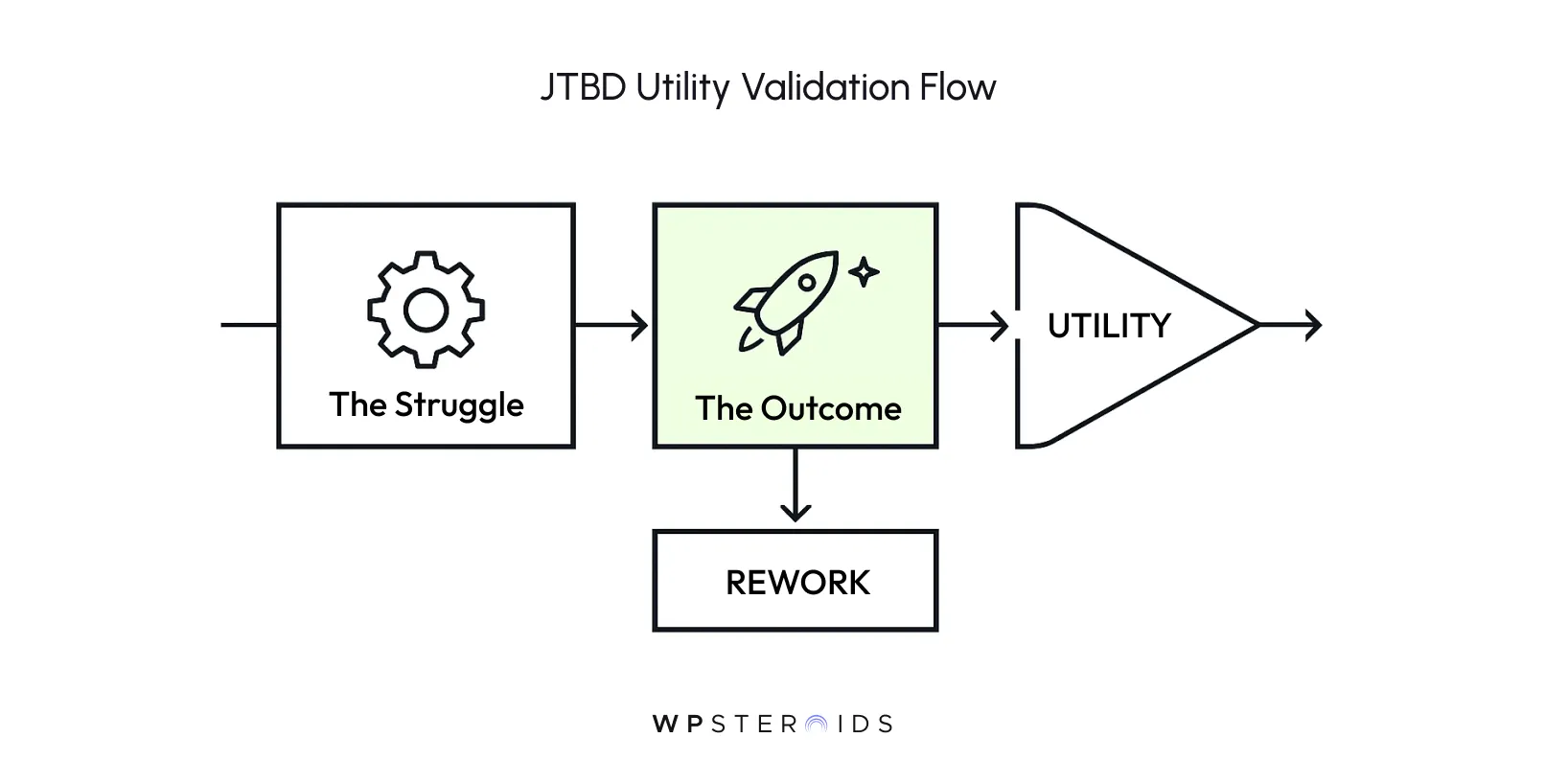

We use the "Jobs To Be Done" framework to validate utility. Instead of asking "What features do users want?", ask "What job is the user hiring our product to do?"

The 60-Minute "Job" Check: Gather your Product Manager, Design Lead, and Engineering Lead. Pick your top feature.

If the answer is a lukewarm "sort of," stop. Do not design the UI. Do not write the code. You have a utility problem. You need to iterate on the core logic until it undeniably solves a real problem.

By applying these laws during the design phase, you ensure that you aren't just shipping features, but actively respecting the user's mental energy.

This is how to improve usability without needing a massive budget—you simply refuse to ship patterns that violate human psychology.

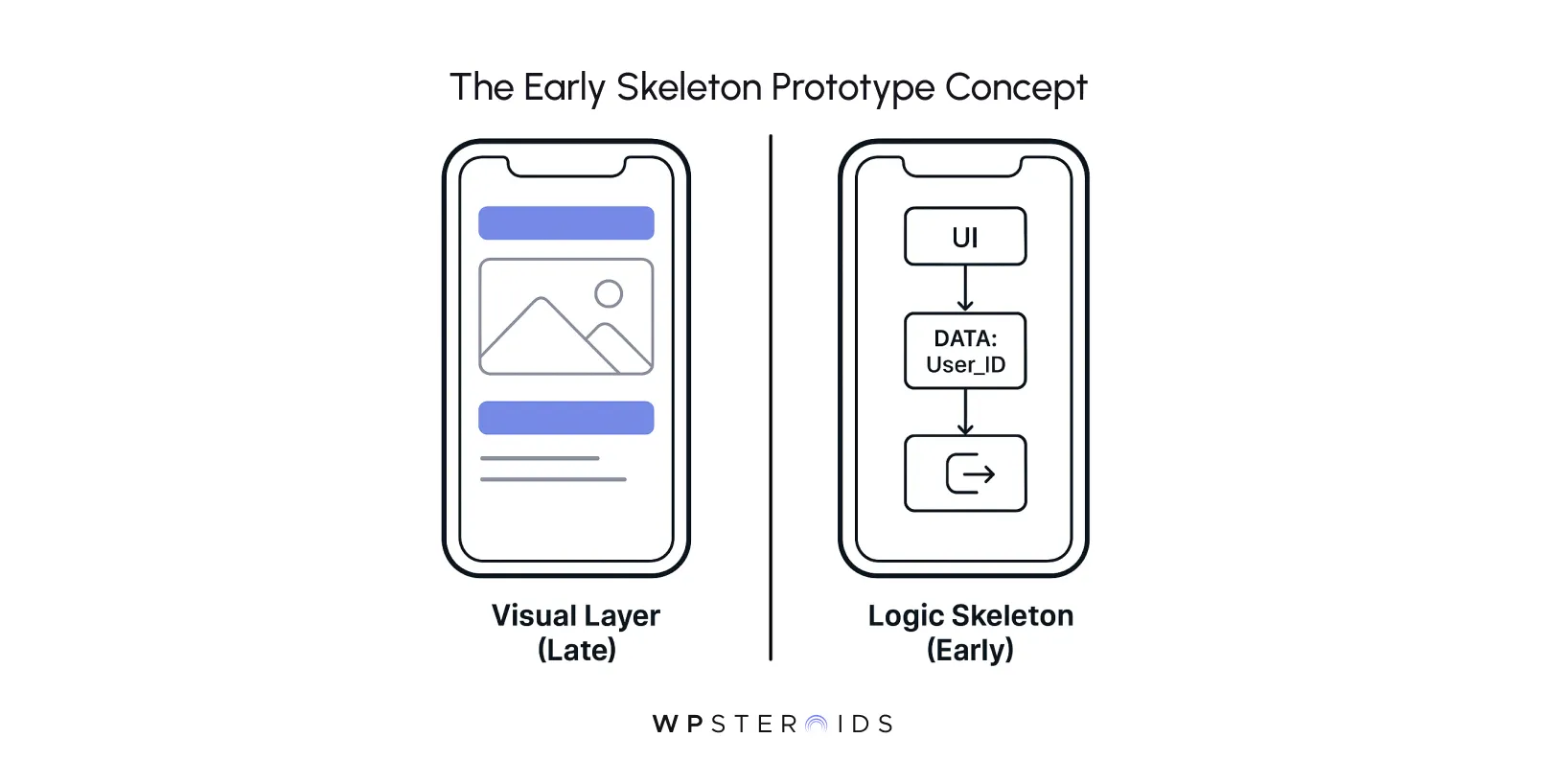

This is where we break the waterfall. This is the tactical core of the entire manifesto.`

To fix this, we need to introduce Early Skeletons.

A functional skeleton needs to test the heaviest plumbing first. It should include:

By stripping away the "pretty," you force everyone to focus on the utility structure. If the skeleton feels clunky or confusing without styling, no amount of drop shadows will save it later.

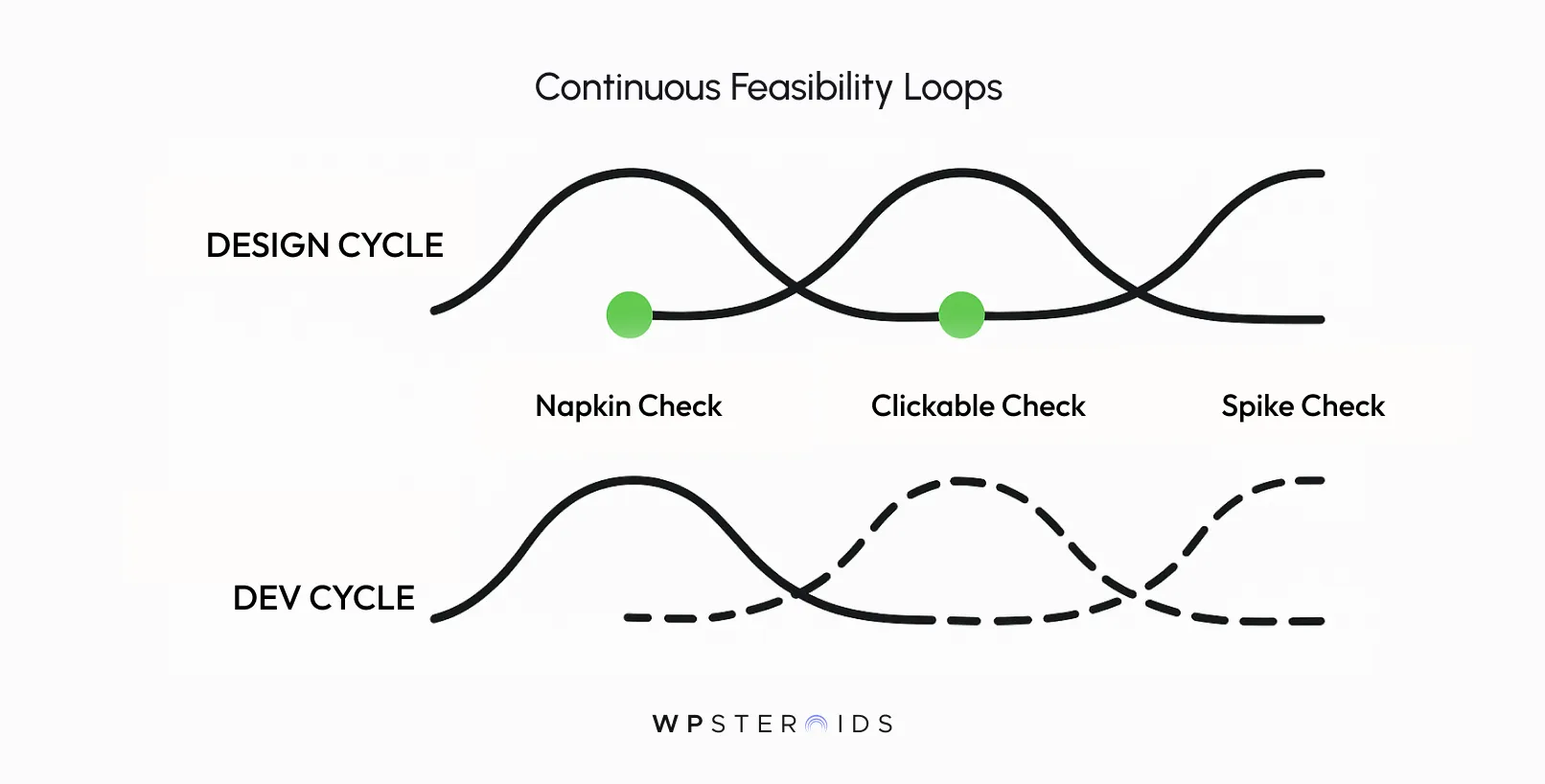

You don't need to pair program for eight hours a day. You just need to implement three specific checkpoints to ensure the utility isn't writing checks that the code can't cash.

You might ask, what is the ux research tool you need to do this? The answer is likely already in your stack.

They will tell you, "I don't get what this button does," which is exactly the feedback you need before you spend three weeks making that button look perfect.

Tools and frameworks are useless if your team is still operating in silos. The most sophisticated "usability vs. utility" matrix won't save you if the designer sits in one room (or Slack channel) dreaming up features while the developer sits in another worrying about database migrations.

The standard workflow usually looks like this: Design Sprint (Week 1) → Handoff Meeting → Dev Sprint (Week 2). By Week 2, it is already too late.

When a designer says, "I want users to be able to filter these 10,000 records instantly," the developer is there to say, "We can do that, but it will require a specific indexing strategy that impacts our timeline. If we limit it to the last 30 days, we can build it in half the time."

This negotiation balances usability, utility, and accessibility with hard technical constraints immediately. Instead of finding out three weeks later that a feature is impossible, the design adjusts in real-time. This prevents the heartbreak of falling in love with a solution that physics (or budget) won't allow.

One of the biggest mistakes in ux design in agile environments is the "Loss of Intent." As a feature moves from a static Figma file to a dynamic React component, small compromises start to chip away at the design.

A 300ms transition becomes instant. A helpful error message becomes a generic "404 Not Found."

To stop this, you need Shared Acceptance Criteria.

By codifying these details, you ensure that the developer treats the "feel" of the product with the same seriousness as the logic.

Twice a week, the developer should show the designer the "ugly" build. It might be unstyled HTML, but it allows the designer to see how users process information in the browser context.

This leverages design psychology for the team—it builds trust. The designer sees progress and feels heard; the developer gets clarifications before they waste hours on the wrong path.

You need to visualize your customers moving through the product as it is being built, not just as it was imagined. This continuous loop turns the "Design vs. Dev" conflict into a collaborative puzzle-solving session.

To truly end the debate between design and engineering, you must move from opinion ("I think this looks better") to evidence ("The data says users can't find the button").

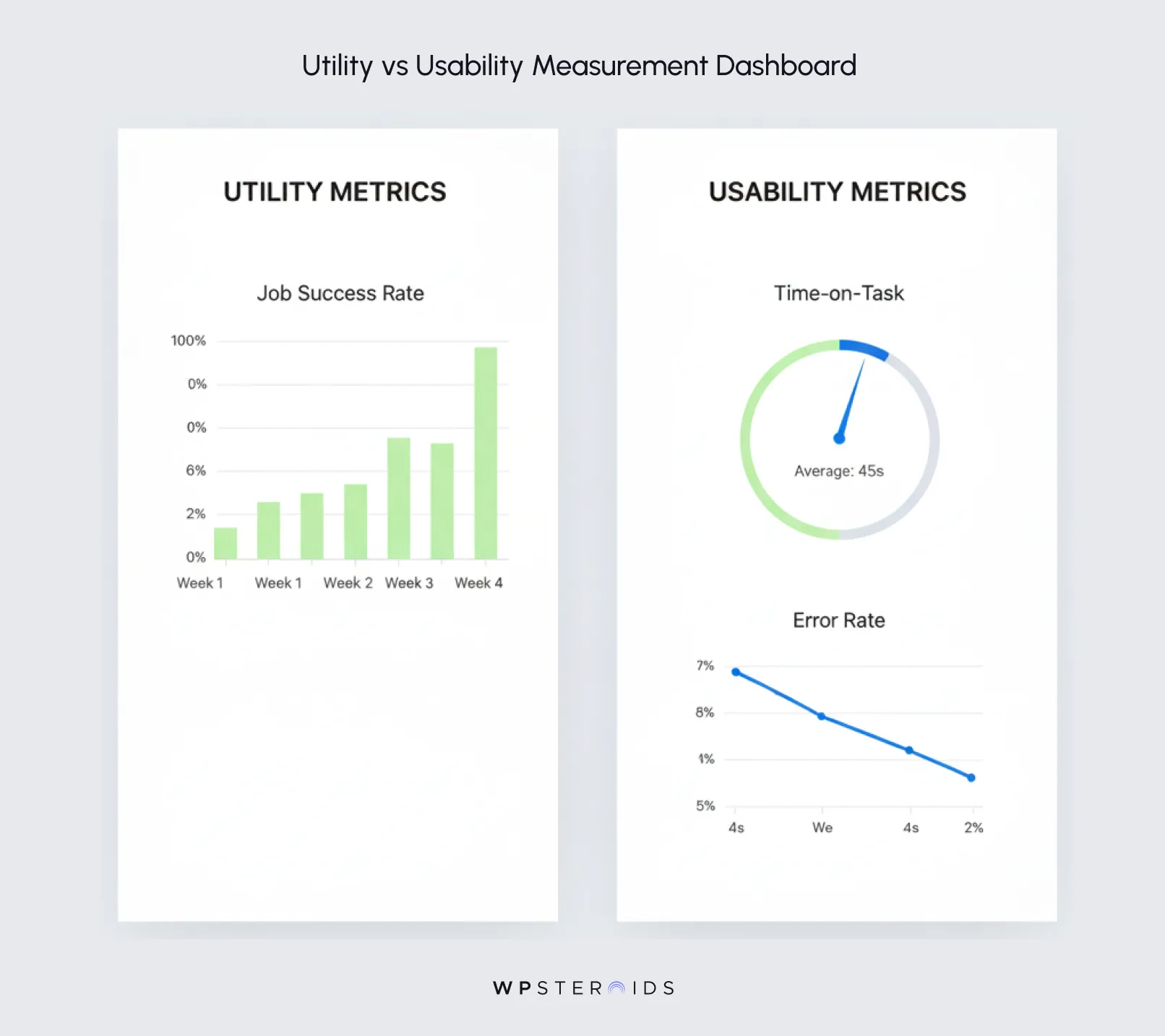

You need a measurement strategy that distinguishes between whether usability is failing or the utility is missing.

Mixing these up leads to the wrong fixes—like redesigning a checkout page (usability fix) when the customer simply doesn't want the product (utility issue).

A user might spend 10 minutes on your site because they are highly engaged (good utility) or because they are hopelessly lost (bad usability).

To measure utility, you must track the Job Success Rate.

If this number is low, but your usability tests show the interface is clear, you have a utility problem. The feature might not be essential, or it doesn't solve the core pain point significantly enough to warrant the effort.

Once you know the user wants to do the job, you measure how hard you are making it for them. This is why usability is important—not just for "delight," but for efficiency and error reduction.

Distinguishing between the two allows you to deploy the right fix, saving you from rewriting logic when you really just needed to fix some CSS.

We started this journey by acknowledging a painful conflict: the tension between usability is (how easy it is) and utility (what it does). For too long, product teams have treated this as a zero-sum game, where you either ship a powerful beast that is hard to use, or a beautiful toy that does nothing of value.

But as we’ve seen, this trade-off is a symptom of a broken process, not a requirement of software development.

The "Early Skeleton" approach offers a way out. By forcing designers and developers to build rough, testable frameworks together from Day One, you validate reality before you commit resources. You stop guessing. You stop hoping. You start knowing.

Remember:

You do not have to choose. You just have to change how you build.

Stop designing in a vacuum. Stop handing off "perfect" mocks to engineers who have to shatter them. Build the skeleton first. Test the logic early. And create a product that works as beautifully as it looks.

If you are tired of the "handoff heartbreak" and want to implement the Early Skeleton methodology in your organization, let’s talk. Stop guessing if your design is feasible.

Book your discovery call with us today, and let’s streamline your product workflow to maximize value and minimize waste.

What is the difference between utility and usability in UX?

While often used interchangeably, the difference is distinct. Utility is about functionality: does the product contain the features needed to solve the user's problem? Usability is about experience: can the user access those features effectively and efficiently? A product has high utility if it can perform the task, but it only has high usability if the user can perform the task without frustration.

What is the "Utility over Usability" effect?

The utility over usability effect describes a scenario where users tolerate bad ux because the product provides essential value that cannot be found elsewhere. This is common in specialized enterprise software or early-stage innovation. However, relying on this effect is risky; as soon as a competitor offers similar utility with better usability, users will switch immediately.

Why is usability important if the utility is already high?

High utility attracts users, but high usability keeps them. Why usability is important comes down to ROI and retention. Poor usability increases training costs, drives up customer support tickets, and leads to error-related data loss. In the long run, ignoring how to improve usability creates "accessibility debt" that makes the product vulnerable to disruption.

How do you prioritize utility vs. usability?

It depends on the product lifecycle. In the MVP phase, utility must be the priority—you must prove the product solves a real problem (usefulness). Once value is established, priority shifts to usability to reduce friction and scale growth. However, the best approach is to use "early skeletons" to test both simultaneously, ensuring you aren't building high-utility features that are impossible to use.

What comes first: Design or Functionality?

Neither should exist in a vacuum. The "waterfall" method of defining functionality (Utility) and then "applying" design (Usability) causes rework. The most efficient workflows use collaborative prototyping, where design and engineering define the utility and accessibility constraints together from day one.