Headless CMS scales and improves WPWhiteBoard’s content distribution, flexibility, and personalization

Bhhavesh Desalhey

It’s the notification you’ve been dreading, even though you’ve been waiting for it all week: "Staging is ready for review."

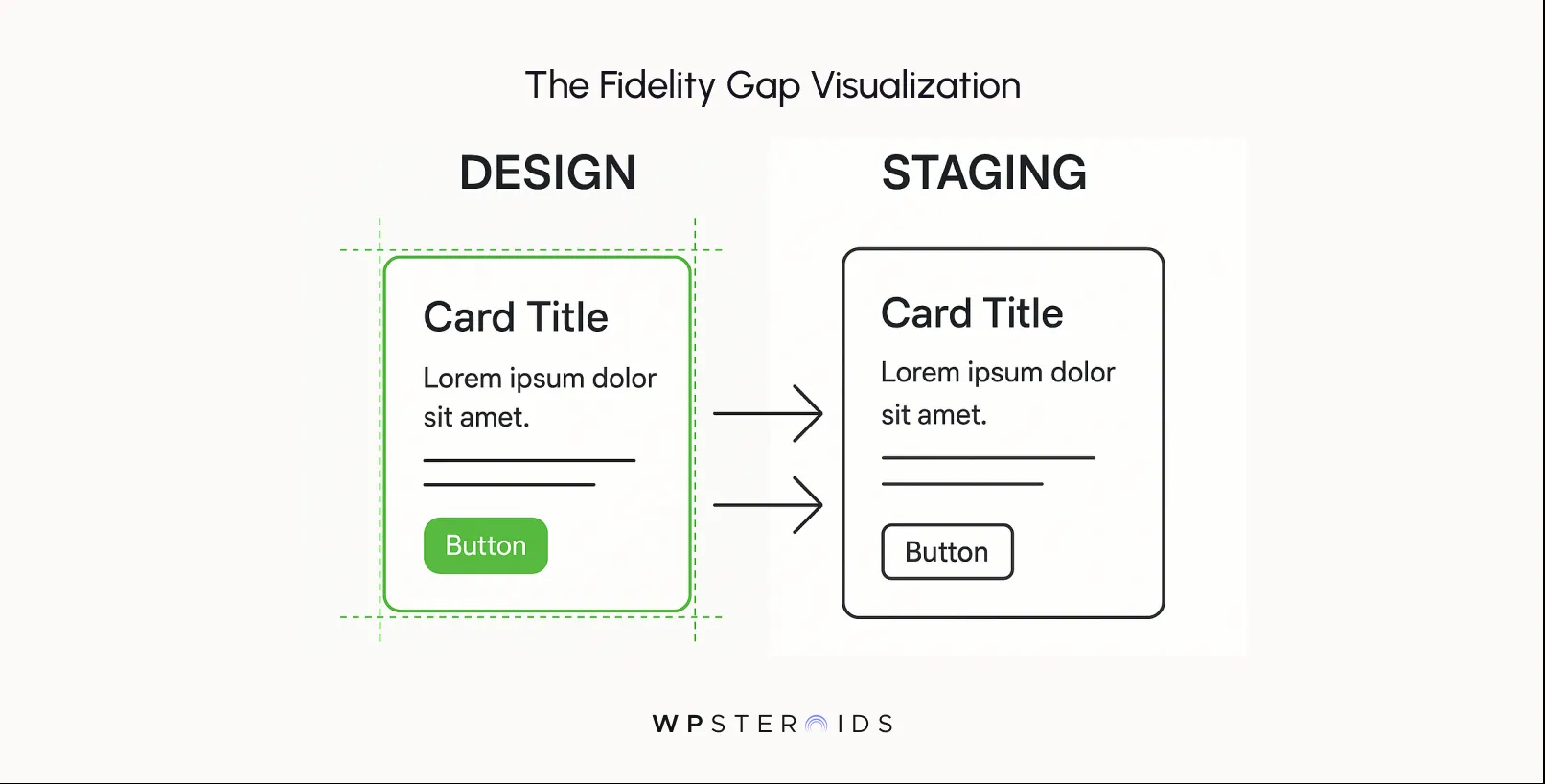

You click the link, and immediately, your stomach drops. You spent weeks obsessing over the spacing, the easing curves on the animations, and the exact weight of the typography.

You built meticulous interactive prototypes to demonstrate exactly how the menu should slide in. But what you are looking at now feels… average. Generic. "Off-the-rack."

The colors are technically correct, but the soul of the design is gone. The micro-interactions you crafted to delight the user? Missing. The layout shifts awkwardly on mobile.

It is the classic nightmare where the designer-to-developer handoff turns your tailored vision into a cheap knockoff.

A successful designer-to-developer handoff relies on a shared design system that explicitly maps design tokens to code, preventing the visual dilution caused by generic "off-the-shelf" workflows.

Instead of a static file transfer, this process demands that designers and developers align on functional logic and technical constraints before development begins.

You’ve likely heard the excuse before: "We can’t do that animation because the library doesn't support it," or "That spacing is standard in Bootstrap, so we kept it." When you hear this, you aren't hearing a technical limitation; you are hearing a priority alignment issue.

Off-the-shelf development teams are often incentivized to deliver functionality, not fidelity. While you are measuring success by how the user feels, they are measuring success by how fast the ticket moves to "Done."

When designers and developers rely on generic component usage without discussing the intent, you end up with a product that feels "mass-produced." It covers the basics, but it lacks the sharp, intentional movement of a bespoke build.

A luxury brand site cannot feel luxurious if it uses the same default button easing as a discount utility app.

By validating design decisions with developers before a sprint begins, you tailor the code to the design, rather than hacking the design to fit a template.

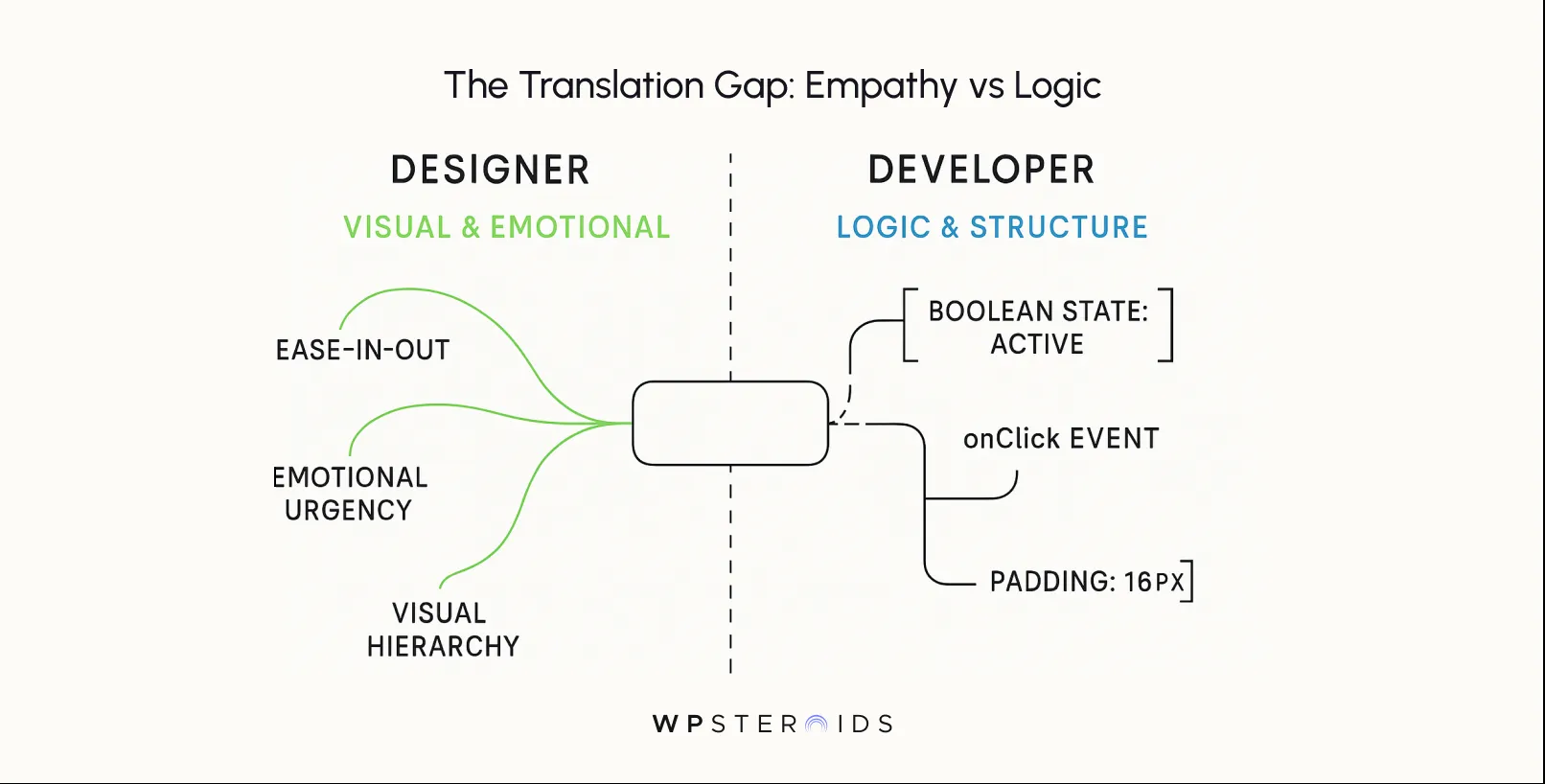

The primary obstacle to retaining your design's soul is often the lack of a shared conceptual framework. Designers are trained to think in user flows, emotional impact, and empathy.

You see a user hesitating at a checkout button; the developer sees a Boolean state change. Because designers and developers speak different languages—one visual and emotional, the other logic-based and structural—nuance is the first casualty.

For a template-first dev team, a design file is often viewed as a "loose suggestion" rather than a strict architectural blueprint. They might examine your carefully aligned icons and replace them with a standard icon set because "it loads faster."

High-quality developers understand that design decisions aren't arbitrary decorations—they are functional requirements.

You know the feeling. You open the staging link, and it works. The buttons click, the pages load, and the text is readable. Technically, the ticket is "done." But emotionally? The magic is gone.

This is the tyranny of "good enough"—a slow erosion of quality that is harder to fight than a blatant bug because it doesn't break the code; it just breaks the experience.

When you hand off a design, you aren't just handing off a layout; you are handing off a feeling. You are specifying the bounce in a loader, the blur on a modal background, and the specific timing of a transition.

Generic, off-the-shelf development approaches view these nuances as "nice-to-haves" that are the first to be cut when the sprint looks heavy. They prioritize the rigid skeleton of the user interface over the muscle and skin that give it life.

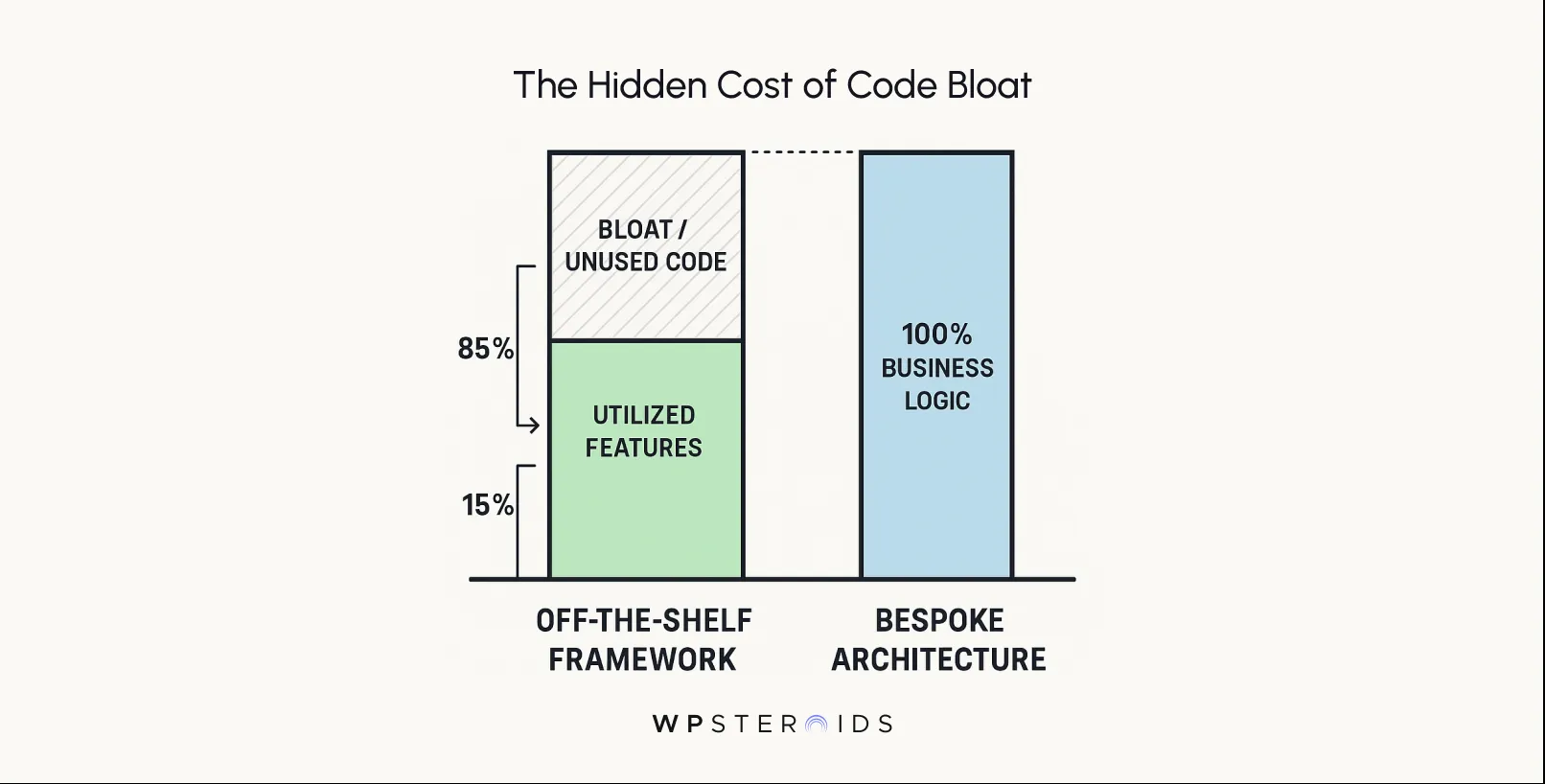

However, you are effectively paying for a massive library of generic code that you don't need, which forces your team to adapt your unique designs to rigid, bloated templates rather than building exactly what your brand requires.

Instead of a lean, bespoke build that amplifies your identity, you get a heavy, generic framework that actively resists customization. This is why you constantly hear, "The framework doesn't really do that."

To fix this, we need to stop treating design and development as separate phases and start treating them as a unified manufacturing process.

The erosion of your design often happens in the margins. It’s rarely a case of a developer refusing to build a feature; rather, it is a series of small, technical compromises that accumulate until your bespoke product looks like a template.

This is the mechanism by which unique brands become indistinguishable from their competitors.

To solve the problem, we must first measure the gap between designers and developers. This gap isn't just about distance or time zones; it is about the "fidelity of interpretation."

When you hand off a design, you aren't just handing off a layout; you are handing off a feeling. You are specifying the bounce in a loader, the blur on a modal background, and the specific timing of a transition.

Generic, off-the-shelf development approaches view these nuances as "nice-to-haves" that are the first to be cut when the sprint looks heavy. They prioritize the rigid skeleton of the user interface over the muscle and skin that give it life.

This leads to a fundamental conflict in resource allocation. Many business leaders opt for off-the-shelf solutions, believing them to be the most efficient choice.

You are effectively paying for a massive library of generic code that you don't need, which forces your team to adapt your unique designs to rigid, bloated templates rather than building exactly what your brand requires.

Instead of a lean, bespoke build that amplifies your identity, you get a heavy, generic framework that actively resists customization. This is why you constantly hear, "The framework doesn't really do that."

You might define "success" as a smooth 60fps animation that guides the user's eye; the developer might define "success" as simply getting the element from point A to point B.

Without a workflow that forces them to respect the quality of the movement, not just the fact of it, the result is a jagged, mechanical implementation that functions correctly but feels broken.

This disconnect waters down your signature style, transforming a product that was meant to disrupt the market into one that merely exists within it.

To fix this, we need to stop treating design and development as separate phases and start treating them as a unified manufacturing process.

A complaint without a solution is just noise.

To move from frustration to control, you need a rigid framework that leaves zero room for "developer interpretation." This isn't about micromanagement; it is about providing a blueprint so clear that building the wrong thing becomes harder than building the right thing.

Here is the technical strategy to structure your handoff, ensuring that what you see in the design file is exactly what renders in the browser.

Before a single pixel is moved, you must establish the logistics of the transfer. If you don't define the medium, the message gets lost.

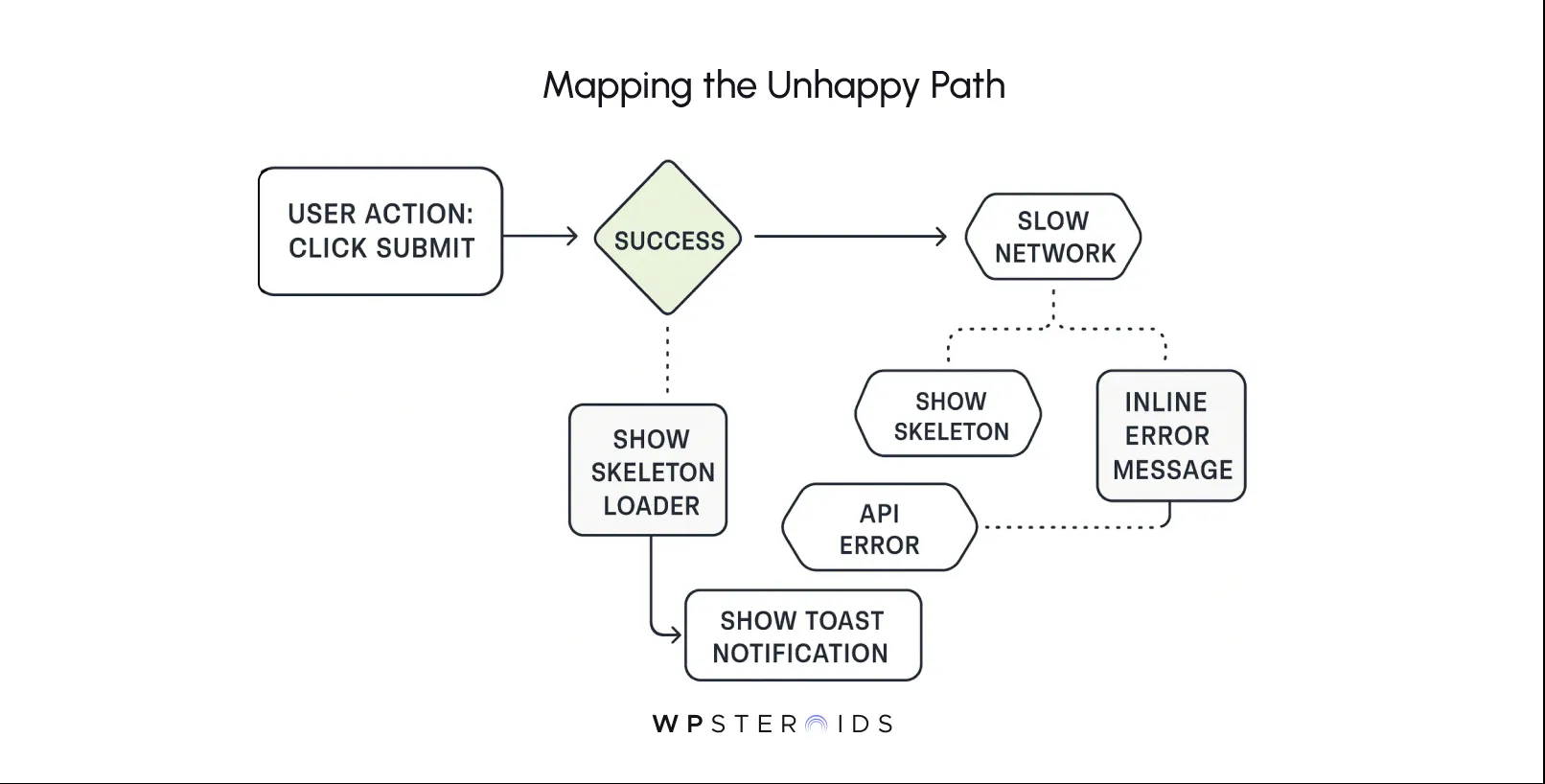

The biggest failure in handoff is assuming a static picture explains dynamic behavior. You must shift from handing off "screens" to handing off "logic."

Speed doesn't have to come at the cost of quality. In fact, if you structure your workflow correctly, the rigorous process is actually faster than the loose one because it eliminates the back-and-forth loops of "visual QA tennis."

The secret lies in automating the boring parts so you can spend your energy on the complex parts.

In that case, you are introducing human error into a process that demands machine precision.

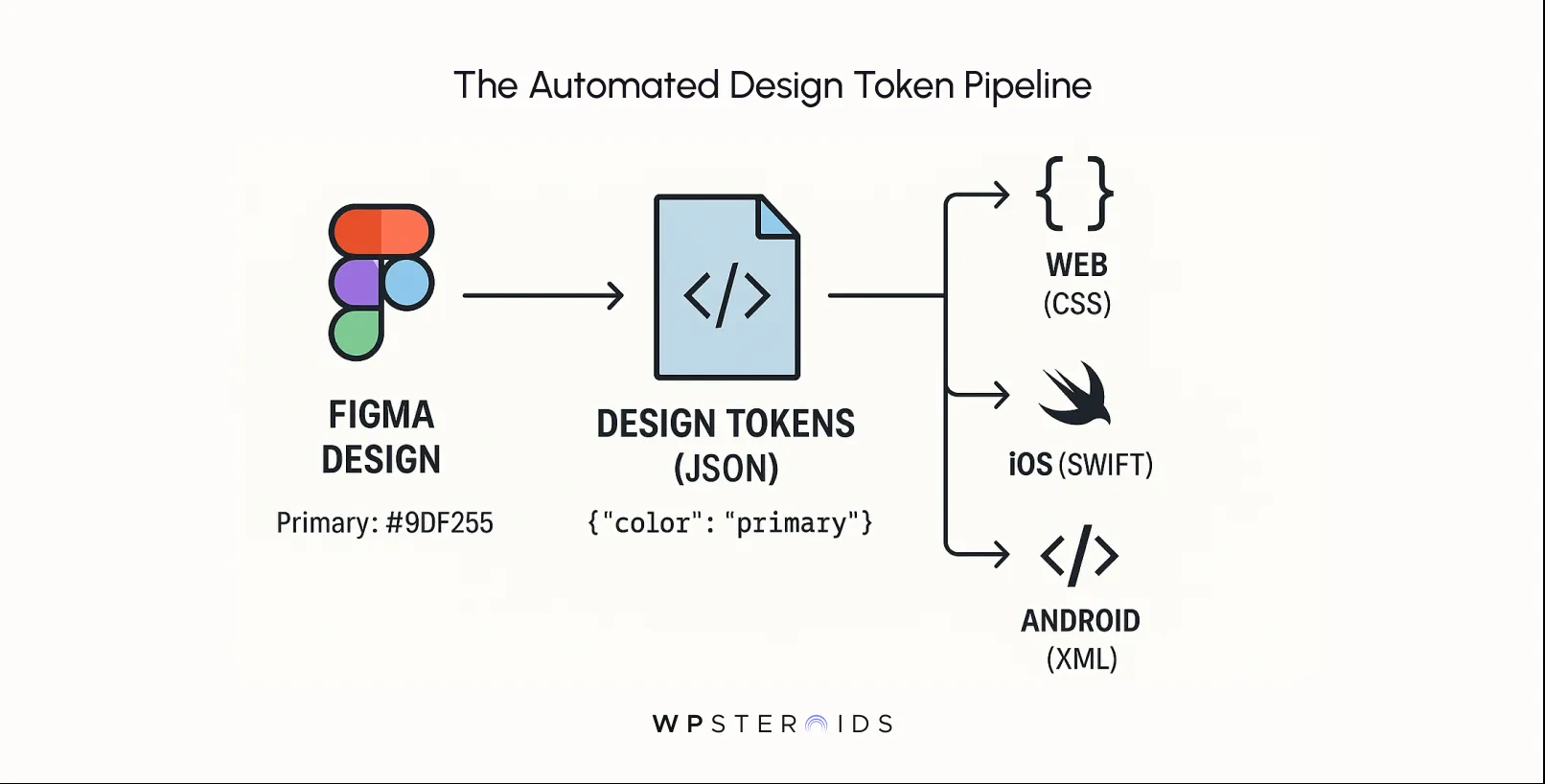

Modern tools allow you to publish your design system directly to a format that developers can use.

If you change "Primary Blue" in your design file, a script updates the token in the code repository, and the change propagates everywhere. This synchronization means shared design values remain identical between the canvas and the codebase without a developer ever needing to "interpret" a color picker. It transforms your style guide from a static document that gets ignored into a living dependency that builds the product.

You need to shift to a mindset of building together from day one. This means bringing a lead developer into the room during the wireframing phase, not just the handoff phase.

Your goal is to ask about technical feasibility before you fall in love with a complex interaction.

This isn't about letting developers dictate the design; it's about understanding the constraints of the medium so you can design intelligently within them.

A five-minute conversation during the ux design and prototyping phase can save three days of refactoring code later.

When a developer can see the component status and documentation right next to the ticket, the friction disappears.

By treating the development team as co-architects rather than just builders, you eliminate the "surprise" factor that derails so many projects.

It starts with a subtle comment from a stakeholder: "Why does this feel... heavier than the prototype?" Or perhaps, "I saw a template online that looks kind of like this for $50."

This is the moment every creative leader fears. It is the moment when the gap between your bespoke vision and the generic execution starts hitting the bottom line.

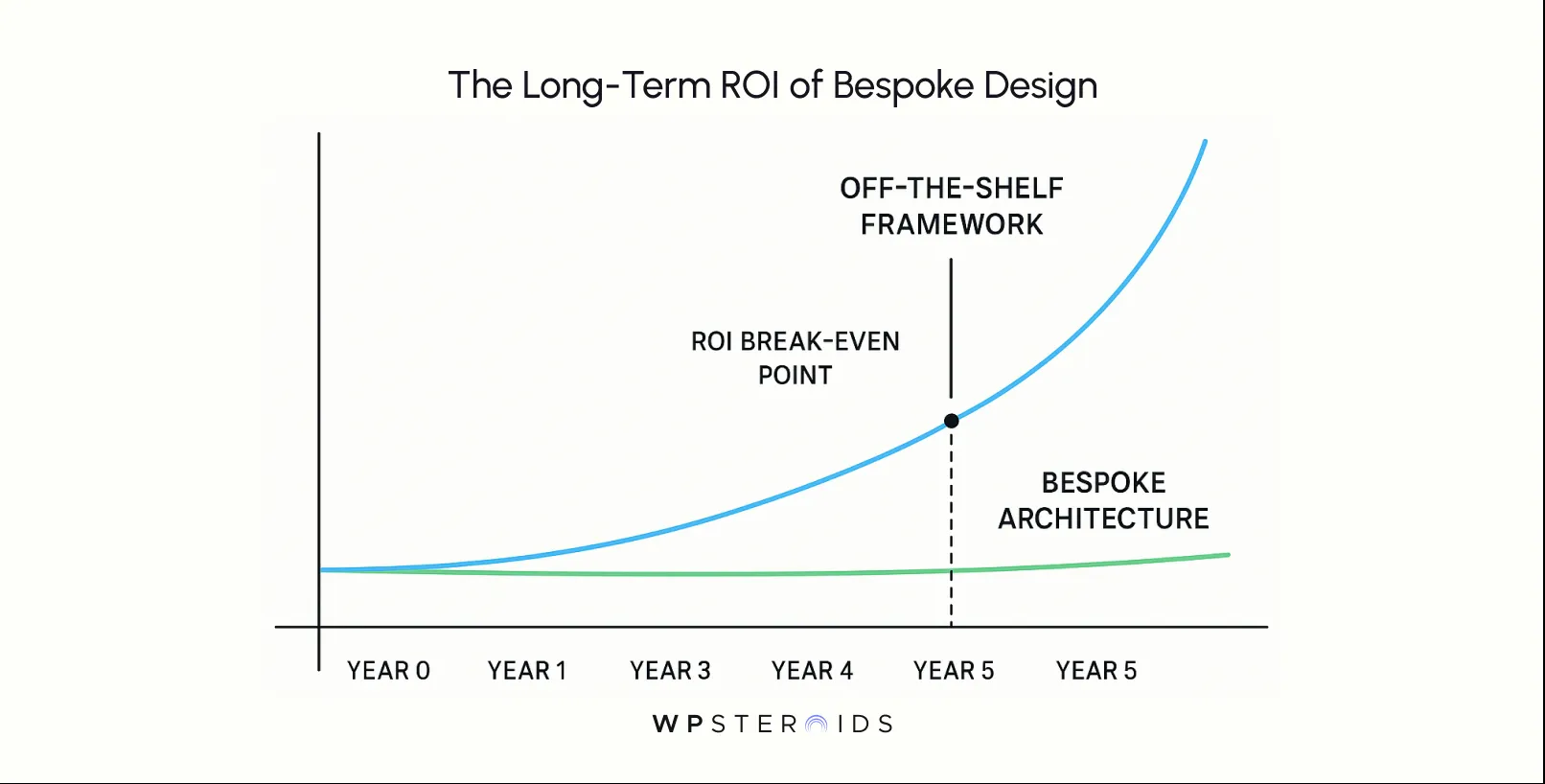

There is a pervasive myth in the boardroom that off-the-shelf development is the fiscally responsible choice. It promises speed and lower initial outlay.

But this "efficiency" is often a mirage that conceals massive long-term costs.

While the initial build might be faster with a template, the costs parity flips by year three due to avoided licensing fees, customization overheads, and the constant need to "fix" the rigid code to meet evolving business needs.

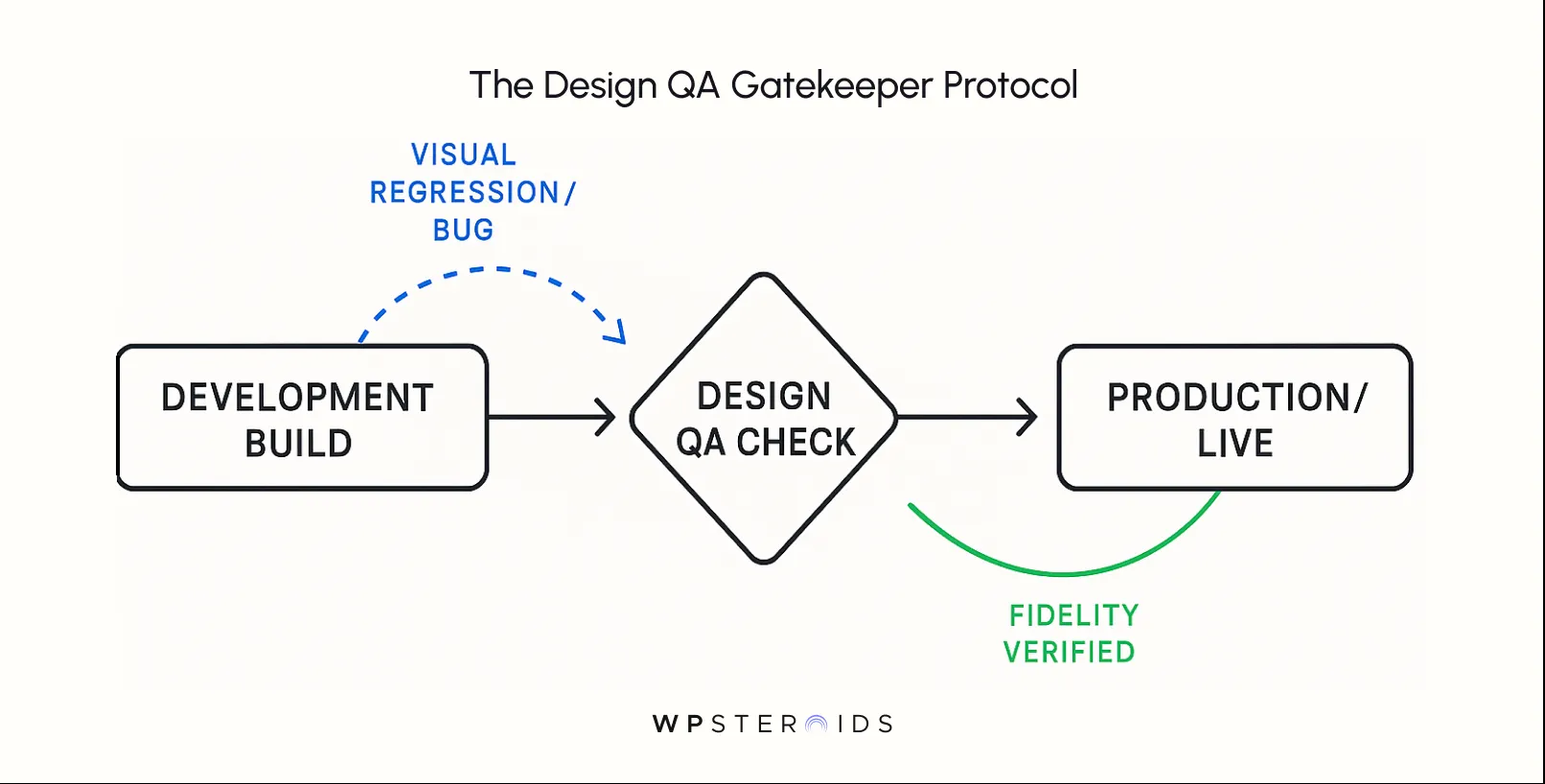

The cost of not eliminating waste designer developer errors is quantifiable. A poor handoff leads to endless rounds of "visual regression" tennis—designers logging tickets, developers pushing fixes, and designers rejecting them again. This churn burns the budget rapidly.

In contrast, a rigorous bespoke process drastically shortens design development timelines in the long run.

By investing in the architecture upfront—ensuring the design is consistent, predictable, and usable, guarantees are baked into the code structure—you eliminate the rework phase. You aren't paying developers to fix alignment issues; you are paying them to ship features.

Ultimately, ensure consistency isn't just about aesthetics; it’s about ROI. A pixel-perfect, custom-coded product scales with your business without the "rent" of technical debt, proving that the cheapest way to build a premium product is to build it right the first time.

To reclaim the sharpness of your original vision, you must insert yourself back into the process, not as an observer, but as a gatekeeper.

Forging Designer-Dev Partnerships: The Key to Uncompromised, Noise-Cutting

The difference between a project that feels like a battleground and one that feels like a collaboration usually comes down to the rules of engagement.

When working with off-the-shelf development teams, the default mode is often transactional: you send a ticket, they send code.

The most common killer of momentum is the "Reply-All" chain or the lost Slack message. You need a rigorous infrastructure for conversation.

By treating feedback and queries as collaborative problem-solving rather than interruptions, you change the dynamic.

When you collect feedback from developers directly about why a design is hard to implement, you often find that a small 5% tweak in design can yield 50% faster code delivery without sacrificing the visual soul of the product.

That is the sweet spot of a true partnership.

The biggest mistake teams make is treating the launch as the finish line. In reality, the moment the code goes live, the entropy begins.

Without a maintenance plan, your crisp, pixel-perfect site will degrade into a patchwork of "quick fixes" and inconsistent updates within six months.

To prevent this, you need to shift your mindset from "launching a project" to "stewarding a product."

The shared design system you built isn't a museum exhibit; it is a living toolset. You must answer the hard question:

Who maintains the design after release?

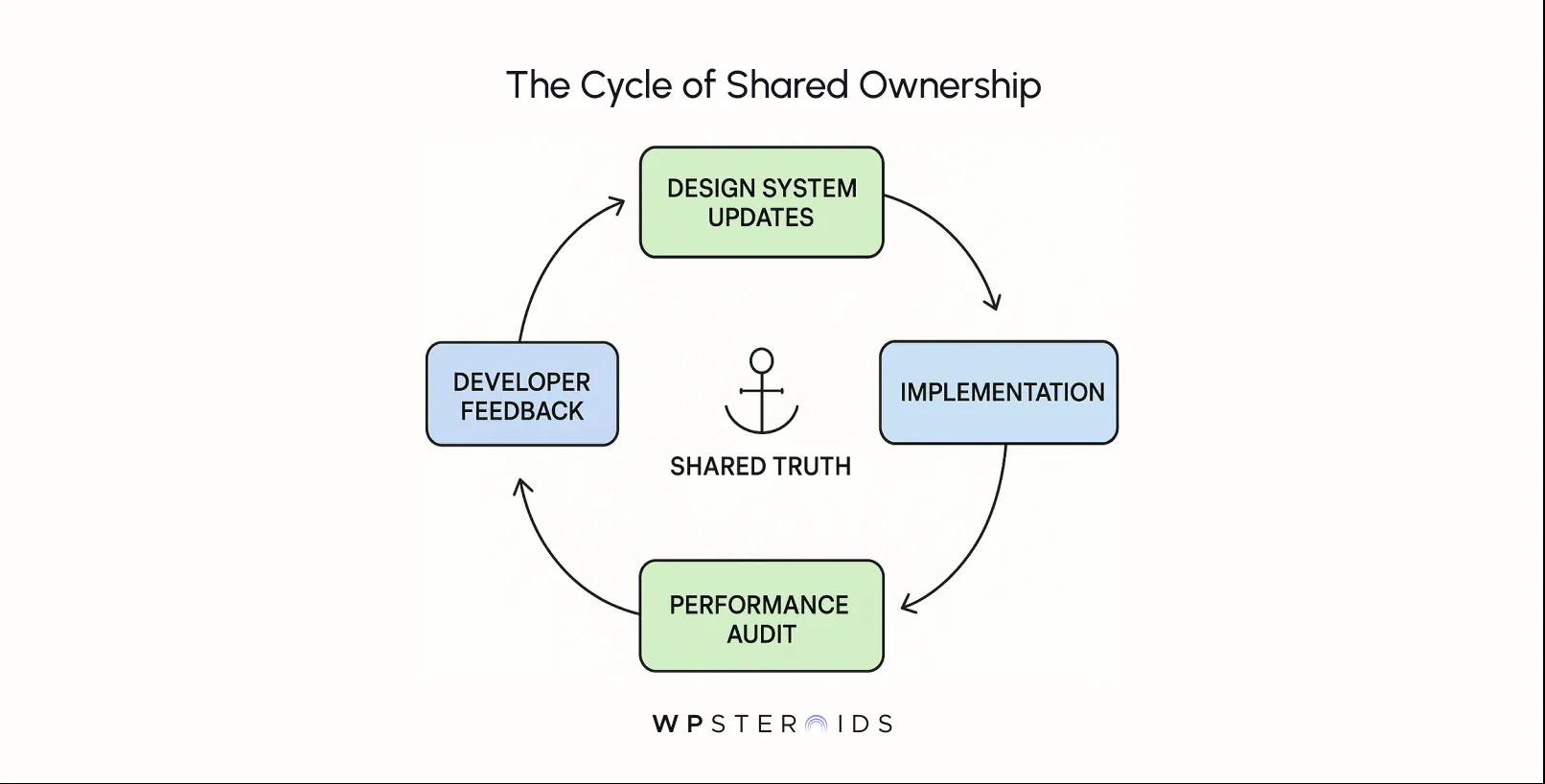

You must establish a lifecycle management protocol where the design system is treated as a product in itself.

This approach requires a shift in company culture. Designers are often viewed as resources that are "freed up" once development starts, but for a high-fidelity product, they must remain attached as consultants.

When you normalize the idea that design validation is a continuous requirement—not just a pre-launch hurdle—you protect the investment you made in the initial build.

The strongest workflow exists when developers create shared design system ownership alongside the design team.

When a developer feels like a co-author of the component library—rather than just a consumer of it—they become the guardians of quality.

Encourage developers to suggest improvements to the system. Maybe a specific animation is causing performance issues on low-end devices; a developer’s input on how to simplify the updates between design and development without losing the visual impact is invaluable.

Ultimately, this fosters an environment where "pixel perfection" isn't a demand from a picky designer, but a shared pride point for the entire engineering team.

When the developer cares as much about the border-radius as you do, you have officially won the war against "off-the-shelf" mediocrity.

In a crowded digital marketplace, the difference between a generic product and a market leader rarely comes down to the quality of the initial idea.

It comes down to the integrity of the execution. You didn’t hire a top-tier design team to create a template; you hired them to build a competitive advantage.

But that advantage evaporates the moment you allow an "off-the-shelf" development process to dictate the fidelity of your brand.

We have explored how the breakdown occurs—not through malice, but through a mismatch of incentives and a lack of shared language.

We have also laid out the blueprint to fix it: establishing a shared design system as a source of truth, automating design decisions via tokens, and replacing the "toss over the wall" mentality with a rigorous partnership.

Don't let a poor handoff process ruin your vision. You have the tools and the vocabulary to demand better. Now, you just need the partner who understands that code is meant to serve the design, not the other way around.

What causes 'good enough' implementations that dilute signature style?

The primary cause is misaligned incentives. Off-the-shelf developers prioritize speed and standard framework utility, while designers prioritize experience and identity. Without a shared system to enforce fidelity, developers default to the path of least resistance.

What should be included in the handoff package to protect visual fidelity?

A robust handoff package must include more than screen mockups. It requires a shared design system containing design tokens (variables for color, type, spacing), component documentation with defined states (hover, error, loading), and explicit accessibility guidelines.

Which tools best preserve design intent during handoff?

Tools that bridge the gap between design and code are essential. Solutions like Zeplin, Storybook, or Figma’s Dev Mode allow developers to inspect values precisely. However, the best tool is a living style guide that syncs tokens directly from design software to the codebase.

How do I communicate non-negotiable visual elements?

Document them as "Acceptance Criteria." Do not leave them as visual implications. If a specific animation easing is critical to the brand feel, provide the exact CSS Bezier curve values and mark them as a blocking requirement for QA sign-off.

How much detail is too much detail for developers?

Developers rarely complain about too much detail regarding logic; they complain about ambiguity. Provide excessive detail on behavior (edge cases, responsive logic, interactions), but avoid redlining every single pixel if you are using a token system, as the tokens should handle the basic values automatically.

How do designers and developers agree on tradeoffs?

Focus on the "why." If a developer pushes back on a complex blur effect due to performance, discuss the user value. Can we achieve 90% of the visual impact with 10% of the "weight"? This turns a conflict into a collaborative problem-solving session.